Forensic Oceanography published the Nivin report.

In November 2018, five months after Matteo Salvini was made Italy’s Interior Minister, and began to close the country’s ports to rescued migrants, a group of 93 migrants was forcefully returned to Libya after they were ‘rescued’ by the Nivin, a merchant ship flying the Panamanian flag, in violation of their rights, and in breach of international refugee law.

The migrants’ boat was first sighted in the Libyan Search and Rescue (SAR) Zone by a Spanish surveillance aircraft, part of Operation EUNAVFOR MED – Sophia, the EU’s anti-smuggling mission. The EUNAVFOR MED – Sophia Command passed information to the Italian and Libyan Coast Guards to facilitate the interception and ‘pull-back’ of the vessel to Libya. However, as the Libyan Coast Guard (LYCG) patrol vessels were unable to perform this task, the Italian Coast Guard (ICG) directly contacted the nearby Nivin ‘on behalf of the Libyan Coast Guard’, and tasked it with rescue.

LYCG later assumed coordination of the operation, communicating from an Italian Navy ship moored in Tripoli, and, after the Nivin performed the rescue, directed it towards Libya.

While the passengers were initially told they would be brought to Italy, when they realised they were being returned to Libya, they locked themselves in the hold of the ship.

A standoff ensured in the port of Misrata which lasted ten days, until the captured passengers were violently removed from the vessel by Libyan security forces, detained, and subjected to multiple forms of ill-treatment, including torture.

This case exemplifies a recurrent practice that we refer to as ‘privatised push-back’. This new strategy has been implemented by Italy, in collaboration with the LYCG, since mid-2018, as a new modality of delegated rescue, intended to enforce border control and contain the movement of migrants from the Global South seeking to reach Europe.

This report is an investigation into this case and new pattern of practice.

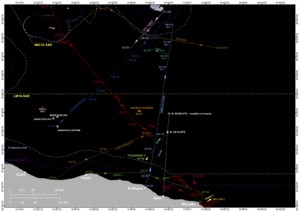

Using georeferencing and AIS tracking data, Forensic Oceanography reconstructed the trajectories of the migrants’ vessel and the Nivin.

Tracking data was cross-referenced with the testimonies of passengers, the reports by rescue NGO WatchTheMed‘s ‘Alarm Phone’, a civilian hotline for migrants in need of emergency rescue; a report by the owner of the Nivin, which he shared with a civilian rescue organisation, the testimonies of MSF-France staff in Libya, an interview with a high-ranking LYCG official, official responses, and leaked reports from EUNAVFOR MED.

Together, these pieces of evidence corroborate one other, and together form and clarify an overall picture: a system of strategic delegation of rescue, operated by a complex of European actors for the purpose of border enforcement.

When the first–and preferred–modality of this strategic delegation, which operates through LYCG interception and pull-back of the migrants, did not succeed, those actors, including the Maritime Rescue Co-ordination Centre in Rome, opted for a second modality: privatised push-back, implemented through the LYCG and the merchant ship.

Despite the impression of coordination between European actors and the LYCG, control and coordination of such operations remains constantly within the firm hands of European—and, in particular, Italian—actors.

In this case, as well as in others documented in this report, the outcome of the strategy was to deny migrants fleeing Libya the right to leave and request protection in Italy, returning them to a country in which they have faced grave violations. Through this action, Italy has breached its obligation of non-refoulement, one of the cornerstones of international refugee law.

This report is the basis for a legal submission to the United Nations Human Rights Committee by Global Legal Action Network (GLAN) on behalf of an individual who was shot and forcefully removed from the Nivin.